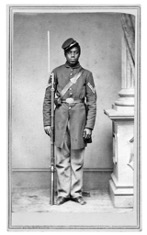

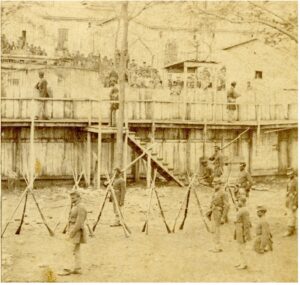

The 108th Colored Infantry Regiment (around 1,000 troops) was assigned to Guard Duty on Arsenal Island in September 1864. The unit had been formed in Louisville, Kentucky in June of 1864 and was composed largely of former slaves and led by white officers. Most of these men were from Kentucky, but a substantial number of these Soldiers were assigned to this Federal Unit from other States as well.

Kentucky, a slave-holding state, had not seceded, but a large part of this State’s population was sympathetic to the defense of slavery. Prior to this point, the federal government treated Kentucky with kid gloves on the subject of slavery in order to prevent losing the state altogether. They were already sending plenty of volunteers south. The Emancipation Proclamation did not apply to them, but recruitment quotas did and by this stage in the war Kentucky was struggling to find enough appropriately aged whites to enroll.

In April 1864, General Burbridge started accepting volunteers who were male slaves to great protest. Loyal slave owners were compensated at below-market rates. Some of these volunteers would eventually form the 108th. Later on, abolitionist recruitment would increase and in March 1865 the families of ex-slave soldiers would be freed. By that point, enlistment had become more about finding a way to free the slaves than a need for more troops. Kentucky would finally acknowledge the 13th amendment that December.

The 108th would replace guards who had enlisted for only a period of 100 days. Unsurprisingly, the “100-day men” did not have enough time to become competent at their jobs and were poorly disciplined. The theory in assigning black guards over white prisoners seems to have been that the guards would be diligent about the job and would be unlikely to be bribed into abetting an escape.

Members of the 108th U. S. Colored Infantry stationed at the military prison at Rock Island.

Courtesy of RIA Museum.

The anger from the prisoners was immediate and hot. In their letters and diaries the guards are referred to as “contraband” and considered the move the gravest of insults. A heinously racist depiction by a prisoner is illustrative of the attitude.

“ [He was] a squat-built negro as black as any ever painted by nature’s brush, low forehead, deep-set eyes, and the elongated jaw of the gorilla, a face denoting at once the low grade of mentality characteristic of the lowest type of the negro–a mere brute.”

Accusations of abuse by the 108th towards the prisoners cannot be verified by reliable sources, though stories would be told of indiscriminate shootings or stringing prisoners along in an attempt to get them to escape, specifically so they would be shot. We do know the deadline was tested more often and the insults and disobedience among the prisoners towards the guards went up substantially when the 108th was posted to Guard Duty.

The guard to prisoner relationship was nasty, but at least the rules were clear. However, the 108th was not treated equally by the other units stationed on Arsenal Island and were not welcome in the community. They were subject to what would eventually become known as “Jim Crow” laws with separate barracks and medical wards. Their commanding officer would complain that his men were unfairly being assigned to fatigue details beyond their fair share and their quarters were not improved like others were throughout the Island. Reports of poor treatment of the 108th by their white colleagues and commanders were all too common.

The guards were not welcome in Davenport. We lack information regarding the viability of the inciting arrests, but this excerpt from the Davenport Democrat gives some idea of the sentiment in this area.

“A DARK TRANSACTION–Two darkies having trespassed on the laws by stealing and riotous conduct in this city, thereby getting themselves locked up in jail, a squad of their dark brethren, some forty strong, who stand guard for a living, on the Island, managed to escape from their quarters last evening and came to Davenport with arms in their hands and wool erect, for the purpose of rescuing their brethren, or to perish in the attempt. . . These “black boys in blue” are getting to think less of “white trash” than ever. It seems as though there was a screw loose on the Island, else so many would not have been allowed to come over here at once to startle the usual peaceful citizens of Davenport into such fearful commotion…”

After the incident, the 108th was banned from going to Davenport. It seems the sentiment was not as strong on the Illinois side of the river as the Argus reported the soldiers “have conducted themselves with great propriety, since they were stationed here.” Granted, Illinois law forbid blacks from being in the State without specific paperwork these soldiers did not possess. So, they went to Illinois less frequently.

Beyond the unfair treatment, 108th included many ex-slaves who had a lack of skills necessary to be independent adults. Few of these soldiers could read, many had never been paid before and as a result had no financial literacy, so they were not equipped to handle con-artists looking to separate them from their money. The officers recognized their men were struggling and losing quite a bit of their money. So, they arranged to begin teaching both reading and financial literacy, so when they left federal service, these men would better equip to make their own way in the world.

Did You Know

The press, always looking to sell papers in the era of yellow journalism, tended to report some fairly wild rumors. One of the most amusing articles was about a prison guard who had a secret relationship with one of the women in the area and had given birth to a child. It would later be clarified; this story was actually a story of a litter of puppies that had gotten really out of hand.

By May 1865, the war was wrapping up and the 108th would be shipped off to the vicinity of Vicksburg, Mississippi for occupation duty. There were some incidents of the unit “foraging” among the local population for rations as their lack of officers and limited support from Washington left them hungry. They also helped to get the newly freed blacks of Mississippi on their feet. For example, two Soldiers of the 108th were elected as financial agents on behalf of a new school in Okolona, Mississippi. The racial ire of the defeated South continued to simmer and opportunistic attacks on the occupying forces and in particular the black troops were a problem as civilian courts certainly had no interest in supporting black troops. One such example is the murder of Private James Roberts of the 108th.

As men from the 108th were discharged, many of them returned to Kentucky. Although, some did end up coming back to this area and settling here. One of those Soldiers who returned was Milton Howard, who lived an incredible life deserving of far more detail than we have space for here. Kidnapped into slavery from Muscatine to Alabama as a toddler, Milton escaped North and joined the military during the war. He later became a part of the 108th infantry and then ended up working on Arsenal Island for more than 50 years. Throughout his life, he learned many languages and was a sought-after preacher.

Did you Know?

Another unusual regiment served on Arsenal Island during the war. The 37th Iowa was composed entirely of men deemed not fit for military service. This was primarily due to age. The men of the 37th were comprised of soldiers from 45 to over 80 years old. They were nicknamed the greybeards. Military inspectors were not impressed by their soldiering skills.