The Mississippi River has been vital for moving cargo through the American heartland since the beginning of America’s westward expansion. This majestic river also was central to Native American civilizations, including the Sauk and Meskwaki.

Today, the area where the Mississippi River system meets the Gulf of Mexico at the Port of New Orleans is the largest Port District in the world when measured by tonnage. The enormous value of river access meant that for many years, recreational use of the riverfronts lining the Mississippi were exceedingly rare in well-populated areas.

The first record of someone settling this part of the current Moline riverfront dates back to 1829, when a man by the name of (no first name given) traveled from St Louis to establish a plantation between what is now 46th to 48th Street, along the Moline riverfront. Stephens brought somewhere between 20 and 70 of his slaves with him. Slavery was not legal in Illinois and locals were terribly upset by the thought of a plantation coming this far north.

Joseph Danforth, one of the upset locals, walked 85 miles to Galena, Illinois, to get a warrant for Stephens’ arrest, as it was the closest place to find a justice of the peace. Given the minimal road network at the time, this trek must have required some major motivation.

Stephens was warned about the warrant, and he decided to pack up and return to the south. In one version of the story, Stephens claimed to have brought his slaves north to let them get used to being free, but they did not like the climate and asked to remain enslaved in the south.

Courtesy of the Rock Island Library

Stephens 1829 Plantation which would become known as Walker’s Station around the 1900s.

Moline: A Pictorial History, By Bess Pierce.

An island located in the middle of the Mississippi off the Moline riverfront came under federal control in 1804, and it was named Rock Island. In May 1816, a detachment of troops landed on the island and immediately began building a fort on the lower end. The installation was named Fort Armstrong. The presence of soldiers diminished over the years, but the war department did not want to release the 850-acre island for public sale.

That did not stop settlers from seeing the upriver portion of the island as the perfect spot for settlement.

Drawing of the Illinois riverfront with Rock Island (now known as Arsenal Island) in the background. The drawing shows the west end of the island where Fort Armstrong was built.

Courtesy Quad-City Times, file photo February 28, 2012

Did you know?

There are two cemeteries on Arsenal Island. The Rock Island National Cemetery began as a post cemetery. It now is the resting place for veterans of the Civil War, World Wars I and II, Korea, Vietnam, Persian Gulf and Iraq. Spouses can also be buried here. The cemetery is enclosed in a highly decorative cast-iron fence. The pickets resemble tree branches with attached leaves, while a gateway arch resembles tree trunks.

Confederate Cemetery

Rock Island Arsenal, Rock Island, IL

There is also a Confederate Cemetery on the island. In 1863, just two years into the Civil War, Congress authorized a Confederate prisoner of war camp on the island. The camp housed 8,594 prisoners at its peak in early 1864. Prisoners who died while in captivity were buried in their own cemetery in 20 rows running north to south. In 1908, the Commission for Marking of Confederate Dead began a program to place distinctive pointed-top marble headstones, inscribed with the name and regimental affiliation of each soldier on the graves. The graves were previously marked with wooden markers.

National /Cemetery Rock Island Arsenal, Rock Island, IL

You can visit the Arsenal Island following special instructions. In addition to the cemeteries, visit the Arsenal Museum and see Quarters One, the largest private home owned by the government with the exception of the White House.

In 1837 David Sears, an ambitious industrialist from the northeast, built a 600ft stone and brush dam on the upriver (east) end of the island that today we call Arsenal Island. He purchased the smaller nearby Benham’s Island as the location for his home, several outbuildings and, of great importance, a steamboat landing. His available water power and access attracted other industrialists to the island. A second dam was built that formed a connection to the eastern mainland. In 1843 Sears and several fellow businessmen laid out a town on that eastern mainland, naming it Moline.

Painting of Moline Riverfront ca. 1843

Courtesy of Rock Island County Historical Society

Just four years later Sears persuaded John Deere and his partners Robert Tate and John Gould to relocate their plow shop to the Moline riverfront. He did this by offering free water power for a period of time and a newly built frame factory. This marks the beginning of the area’s industrial growth.

John Gould, originally from Massachusetts, learned about being a successful businessman from John Deere. he worked for Deere as a bookkeeper and office manager n Grand Detour. When he decided he was ready for a business venture of his own, he approached his brother-in-law and woodworker, D. C. Dimock to become his business partner. DeWitt Clinton Dimock, not yet 20 years old, left Connecticut in 1840 to seek new opportunities in the west. He already owned an interest in a sawmill on the island where he turned bedsteads. Using this space, the two men began producing bedsteads and chairs. They used the income from the sale of these items to build their own shop and buy new equipment.

The new equipment allowed Dimock & Gould to build a wider variety of items. At the time, if settlers needed woodenware, the items had to be ordered from out east. The items then were shipped down the east coast, through the Gulf of Mexico and up the Mississippi River at a considerable cost. In 1853 Dimock & Gould began manufacturing a variety of wooden tubs, washboards, pails and churns. During the Civil War, they had a great customer nearby when the decision was made to build a prisoner of war camp on the island.

In 1862 Congress passed an act establishing a national arsenal on the island. Dimock, Gould and other companies who built on the island without leases or land ownership were told to leave. Dimock & Gould and other companies packed up and moved to the Moline riverfront.

Industry was beginning to fill the riverfront. Dimick& Gould built a sawmill a two-story warehouse, 2 shops for manufacturing tubs, and 8 brick “dry houses” for seasoning the umber. Within 5 years the sawmill had 2 additions. To get the lumber they needed to make their products, Dimock and Gould joined 17 other companies to form the Mississippi River Logging Company. Lumber would be harvested, in Wisconsin at this point in time, then the logs would be sent down the Mississippi in huge log rafts pushed by steamboats. Large booms were placed out into the river to catch the logs coming to your business.

1889 Perspective Map

Courtesy of United States Library of Congress

As seen in this map, Dimick & Gould had a large presence on the Moline riverfront. They occupied 12 buildings spread over 15acres of land. So much woodenware was being shipped that the company ordered six custom-built freight cars, longer than regular cares and brightly painted to advertise “Moline Wooden Ware.” Their 1882 annual report gave production totals of 440,000 pails, 119,000 tubs, 84,000 washboards, 10,000 churns and clothespins by the hundreds of thousands.

Both fire and water proved to be problematic for factories along the riverfront. The low areas would flood in the spring as the snowmelt flowed down the river. At all times of the year, sawmills and woodworking shops were susceptible to fire. And there were a lot of fires. Businesses along the riverfront: Dimock & Gould, J.S. Keator & Son, Deere & Co and Moline Wagon Co all had their own pumps, water mains and hydrants. As a group, they offered to pump water to fight fires any place in the town without charge for 3 years, if the city would lay mains to the factories.

Did you know?

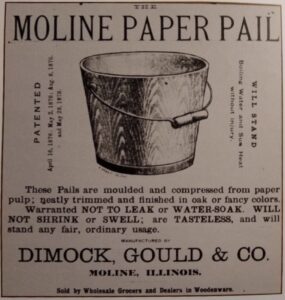

In 1887 Dimock & Gould started making paper pails. Paper pails were designed to overcome the shrinking or swelling of the wood in wooden pails leading to leaks or a full falling apart. Paper pails were made from straw with hemp fibers added, which was reduced to pulp by cutting engines and oven vats. When the pulp reached the proper consistency, the pail was pressed in a mold, dried in a kiln, and subjected to a boiling process in a rosin solution that rendered it impervious to water. By 1889 the output was 1,200 paper pails a day. An original paper pail can be seen on the second floor of the house museum at the Rock Island County Historical Society, 822 11th Ave., Moline, IL.

This riverfront away from the industrial area was not a place to build important buildings because flooding was not uncommon. In fact, much of it was left in its natural state. But it is hard for people to resist being in or near the water. In the 1880s swimming near the facilities of Dimick and Gould was popular enough to draw suggestions that actual facilities be built there. An 1894 map of the area identifies the Riverside Driving Club in the area north of Riverside Cemetery. A variety of fishing shacks could be seen up and down the shoreline. More impressive, A 500-foot riverfront area owned by the Moline Foundation was used for waterborne activities by the Boy Scouts. In 19141 the Sea Scouts hosted a sailing regatta attended by 350 scouts and their leaders from four states. Twenty-seven sailboats were launched for team regatta races, officers’ races, and landing and mooring competitions. More than 200 scouts were given boating and sailing lessons. A Sea Scout Ball was held Saturday evening with special music presented by an octet from the S.S. Hornet based in Detroit.

Scouts Regional Regatta on the Moline Riverfront September 1, 1941