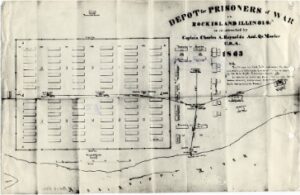

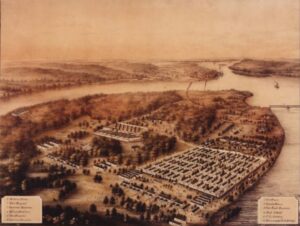

The Rock Island Arsenal was officially established on July 11th, 1862 following the attack on Fort Sumter in South Carolina in April 1861 which officially started the American Civil War. Due to funding and material constraints, the Arsenal construction was slow to start. By 1863 the Federal Government was overwhelmed with Confederate prisoners after ending the prisoner of war exchange program with the Confederacy. More than 600,000 prisoners would eventually be captured during the war.

Early in the war, both sides relied on the traditional European system of parole. Essentially, the captured troops were allowed to go home in exchange for swearing not to take up arms again. This typically was a part of a formally arranged prisoner exchange. By 1863, this practice was halted for 3 reasons.

- (1) Conscripted militia were surrendering without fighting “hard enough”, so they could be paroled and sent home.

- (2) The Union realized some Confederates were breaking their parole and returning to fight or at least making themselves useful to the Southern war efforts in other ways. The Union had more people to spare, so a fair prisoner exchange benefited “Johnny Reb” more than “Billy Yank”.

- (3) The breaking point came once African American troops started seeing combat and then some were captured. The Confederates refused to treat black troops as POW’s or include them in exchanges. Stories of abuse and the massacre at Fort Pillow helped ensure the policy stayed in place until 1865.

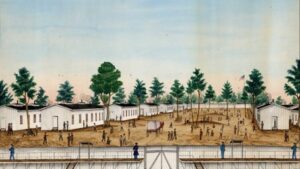

Construction of the camp began in August 1863, but by the time the first prisoners arrived from Chattanooga in December, it had not yet been completed. Throughout the War, the prison would always struggle with its infrastructure. In the first three months, the prison was open almost 1,000 prisoners died from disease (mainly smallpox) and exposure to the cold.

Did you know?

Death by disease was not easily avoided by Civil War soldiers, whether or not they were imprisoned. 2/3 of the more the 660,000 deaths during the war were caused by some variety of diseases. This is what happens when you pack large numbers of people together who did not yet understand what good hygiene meant and did not have the capacity to keep themselves and their belongings thoroughly clean, even if they had the disposition to do so. This varied population of soldiers had not previously been exposed to many childhood diseases before joining the army, because of their limited exposure to other people outside of where they lived.

Old Prison Hospital during Spanish American War located on Rock Island Arsenal. Courtesy of RIA Museum.

In the spring of 1864, the Union built a hospital complex and water system which substantially improved the medical treatment for the prisoners. In fact, 967 soldiers died within the first four months of the prison opening.

The following 1,000 deaths would happen over the remaining years of the war. Most of these soldiers are currently buried in the Confederate cemetery which is still maintained on Arsenal Island.

After the war, many in the South felt the prison in Rock Island was particularly horrible. In many instances, this prison was regularly compared to the infamous Andersonville prison. The hyper-successful novel “Gone with the Wind” references a character as having survived Rock Island and did a great deal to perpetuate this myth. In the book, 75% of all Soldiers sent to Rock Island did not make it out alive. That statistic was actually 15%. Andersonville was 29%. Andersonville was particularly notorious for being unable to feed the inmates. So, malnutrition and scurvy were the leading causes of death. The diet of a prisoner in Rock Island was far better than at Andersonville. Indeed, the Rock Island Arsenal Prison had a better mortality rate than the average Union POW camps of that period. A prisoner also had a higher chance of survival than being in a non-combat role in the Confederate Army due to high rates of disease.

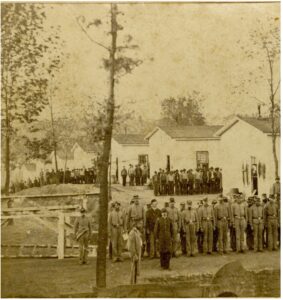

When the first prisoners arrived on a bitterly cold December day in 1863, they generated “intense excitement never to be forgotten”. Hundreds of locals watched the “Rebels” unload from the train and were marched to the stockade. Apparently, the business community was pleased with having the prisoners housed on Arsenal Island. After all, at its height, the prison held over 8,000 people. This number does not include all of the guards and staff on the island. It is interesting to note that during the Civil War, Davenport’s population was around 15,000 people So, this swell in population created enormous demand for all sorts of goods and services.

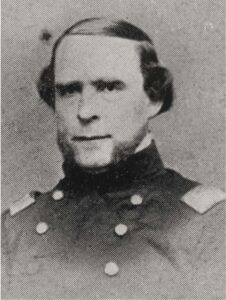

There are many reports of locals taking pity on the captives and then gathering food and blankets for them. Local Copperheads (a term used for a faction of the Democrat party in the Northern States who opposed the American Civil War and wanted an immediate peace settlement with the Confederate Government), most notably Mrs. Buford and Boyle, arranged for “Liberal donations of clothing continue to be made by the good ladies of Kentucky, Tennessee and by kind friends who do not reside far from this place.” They also were known to aid prisoners who managed to make their escape. The Rock Island Argus, a known Copperhead supporter, was very harsh towards Colonel Johnson, the Camp’s Commandant. The paper’s editor accused him of War Crimes in how the prison was run. The Iowa run papers were more generous to Colonel Johnson.

Imprisonment was not a pleasant experience and prisoners were subject to harsh discipline. The day would begin with a roll call, in order to identify any escapees or overnight deaths. There was a prison library stocked by local donors. Church services were held by visiting ministers and chaplains. Many prisoners made buttons and art from shells, as well as other materials to sell. Prisoners were allowed to hold judicial proceedings to try crimes like theft.

Prisoners would be put to work (on a volunteer basis) building a sewer system and then making other improvements to the post. They would be paid 10 cents a day and receive increased rations. The going rate for a civilian laborer at this time was $1.50/day. Work trips outside the stockade were one of a few ways prisoners used to escape. Later in the war, the prisoners would be offered the opportunity to renounce the Southern Cause and swear their loyalty to the Union. More than 1,000 would join the Navy and be sent to Boston and another 1,700 would be recruited to the Army with the intention of sending them to fight in the Western frontier. These “Galvanized Yankees” would be sequestered in the “Calf Pen” and receive more robust rations until they were shipped to their next post.

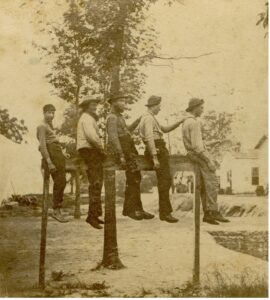

Corporal punishment was common in this era though flogging had been outlawed in 1861. A Confederate who broke the rules or attempted to escape was subject to marching in place for several hours, strapped by their thumbs or wrists to the fence and forced to stand on tip-toe for several hours, chained to a ball and chain or ride on “Morgan’s mule.” This last device was a one-inch board set on its edge at a height of about eight feet above the ground. Prisoners were forced to straddle this device for several hours. The guards could face all the same punishments up to and including the mule.

Four feet inside the stockade wall there was a “deadline.” If you cross this line you were shot. Each incident was followed by an investigation and exoneration. There was apparently a surge in activity at the deadline after the arrival of the “108th United States Colored Troops.” The prisoners, according to their diaries, found themselves guarded by Black men. To them, this was the most galling aspect of prison life. Many of them dared the guards to shoot. They eventually learned the physics of hot lead, which trumped their social conditioning about the world.