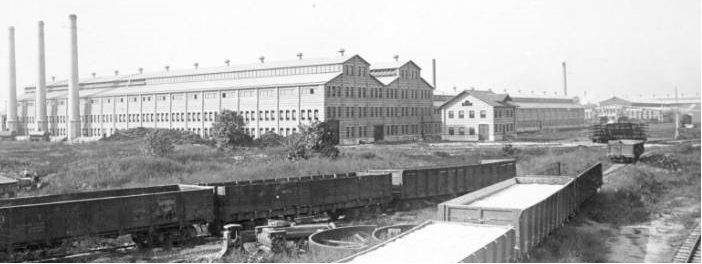

As the Bettendorf Company established itself in an area that was unpopulated at the time, there was a substantial need for infrastructure and people. Early on, the Bettendorf volunteer fire chief recalled wagons mired in mucky clay roads, traveling through farmland to and from the factory. The overloaded roads were so severely inadequate for the volume of traffic and harsh weather conditions that sometimes even pedestrians would get stuck.

Austrian immigrant, Andy Haber, a skilled molder from that empire enticed by good wages and the promise of social mobility to Bettendorf, recalled walking home but being unable to find it in the darkness of wilderness just about a mile from the factory. It really was the frontier edge of industrial America.

The Bettendorf company made investments into the community, building housing for their workforce and a hotel to serve temporary housing needs. The company also made some efforts in support of their labor, which was impressive during a time where there were exploitation, unionism and socialism on the rise, especially in the Midwest.

In 1924, J.W. Bettendorf created a Mutual Aid Association, which functioned similarly to various primitive supplemental insurances and Social Security. Essentially, workers paid into a fund, and should they be incapacitated by injury or illness, they would then be supported by the MAA. Bettendorf observed that insurance companies could too quickly determine accidents to be the workers’ fault, and efforts to pass the hat relied too heavily on personal popularity to succeed. This must have been particularly difficult for those who had recently immigrated to the area.

The work taking place in this factory was not safe. The company had its own foundry, and molten metal and flying shavings were very real hazards. Specific records of the injury rate at this facility have not yet been found, but by one estimate, there were around 10,000 serious workplace accidents in Iowa throughout 1910.

In 1900, the average hourly wage for a factory worker was 20 cents per hour, and the standard workweek included six 10-hour days. This resulted in about $600 in earnings per year. Today, that equates to about $19,000 per year. During the same time, the Iowa Railroad Industry manufacturers paid an average annual sum of $536 per worker.

Unsurprisingly, many workers in industrialized cities lived below the poverty level, and it was common for young children to have to work as a result. The first federal Child Labor Law was not passed until 1916, though it would be struck down in court. The issue was not stabilized until the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938.

Outside of work, folks living in Bettendorf had 10 grocers, five meat markets, five restaurants, three hotels, three ice dealers, and two fuel dealers. If one was in need of other items, such as clothes or furniture, they would travel to Davenport; there was specific and successful lobbying by local retailers to keep out traveling salespeople.

During this time, prohibition was gaining steam. Davenport and Bettendorf never were particularly pro-prohibition. The prohibitionists did, however, enact laws limiting the number of retail liquor establishments. This affected Bettendorf more than Davenport because the town was still growing and there were fewer establishments to be grandfathered in.

In Davenport, the area known as Bucktown became particularly infamous for its debauchery. On May 2, 1918, the secretary of the Army actually ordered that “all saloons and Baudy Houses within half a mile of Rock Island Arsenal must close within 36 hours.” The of those particular areas dispersed the demand for such entertainments never reached similar heights.

Trade union membership and socialist political ideologies grew in the first couple of decades of the 20th century. Generally, the supply and demand balance for labor in Scott County favored labor, and wages tended to be better than elsewhere in Iowa. Labor relations, while not always amicable, did not rise to the same degree of animosity that characterized Chicago during this era.

Did you know?

Socialists carried thecity elections of 1920 and engaged in substantial public works programs to combatunemployment. The construction of storm sewers was a particular benefit toward the maintenance of notoriouslymuddy roads. The expense of these projects is credited with thelosses in subsequent elections

After World War I, the Bettendorf Company recruited 150 Mexican immigrants from Juarez. Recruits came to the area with family and friends who also sought work with the company. Faced with housing discrimination and few options for other work, this community was essentially stuck in company-built housing in the Holy City Neighborhood (named for the prevalence of children named Jesus in that area). These issues created segregation within other neighborhoods throughout the region, too.

Because other companies refused to hire folks from this community, Bettendorf Wheel could often get away with paying workers low wages. While folks living in Holy City certainly were quite poor, conditions were substantially worse for Mexican immigrants. Members of this community for years often ended up living in railroad boxcars in the Cook’s Point neighborhood and across the river in Silvis, Illinois, which obviously had no essential amenities such as heat or plumbing.

While this area did not actively repatriate immigrants to Mexico during the Great Depression, which occurred in other Midwestern cities at the time, major restrictions on housing and unemployment aimed to drive many members of this proud community out of town.