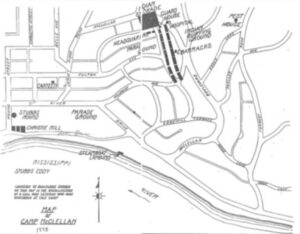

So, how does the Sioux Uprising connect to Davenport? After 1,600 Sioux people arrived at Fort Snelling, Major General John Pope ordered General Sibley to send about 300 Sioux prisoners to Camp McClellan — including 277 men, 16 women, two children, and one Winnebago man — to serve their sentences. At the time, Camp McClellan was focused on the Civil War, so soldiers there hastily formed a new camp at the top of the bluff within their acreage, and called it Camp Kearney. This separate camp needed to be developed, so there was a separate chain of command and mission established to do so.

Prisoners arrived in Davenport by steamboat in April 1863. Upon arrival, they were sent up the steep hill of Crestwood Avenue chained to each other, two by two, toward the newly formed Camp Kearney. As news of their arrival spread, people in the area came to the camp to watch the Native Americans. General Roberts, who was ordered to oversee their safekeeping with Captain Littler, said: “The had turned into a menagerie of sorts. As many came to amuse themselves watching the antics of the ‘savages.’ They were a spectacle to watch for the residents of Davenport due to their culture.”

According to the Davenport Democrat, the housing was described as follows: “The pen made for their reception is 200 feet square and encloses four buildings, formerly barracks. The bunks are all taken out. Two of these barracks are occupied by the prisoners as sleeping quarters, one is assigned for hospital, and the other is the guard house of the post.”

Did You Know?

An escaped slave by the name of Joseph Godfrey found refuge with the Dakota and fought alongside them in Minnesota. Escaping execution by testifying against other Dakota, he was imprisoned in Davenport for 3 years before living out the rest of his days on the Santee Reservation in Nebraska.

Limited space made it difficult for prisoners to avoid disease. Many people at the camp either succumbed to diseases such as influenza and smallpox, or the brutal cold of the winter, because they were not provided with stoves in their barracks. In March 1863, it was reported that 50 Sioux died because of poor living conditions.

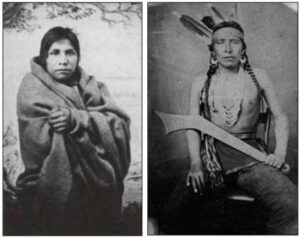

Prisoners were forced to do hard labor while they were detained, including digging wells, chopping wood, grading and sweeping the grounds. Women who were sent to the camp helped with the cooking and took care of the men as they grew sick. Throughout time, some of the Sioux were released while others were ordered to camp as additional convictions came down from Fort Snelling.

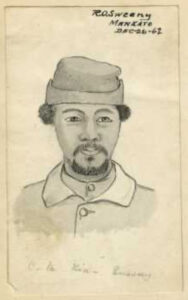

Little Crow’s son, Wowinape, was arrested in late July 1863. After his trial, he was sentenced to time in Davenport. He did survive his time there. Jerome Big Eagle was a leader of the Mdewakanton Tribe, and was an active leader in the uprising. His name was on an 1864 pardon list, and he was released in December of that same year.

As time passed, the area grew more used to the prisoners, and some of the restrictions were slightly eased. In August 1864, President Lincoln pardoned 27 prisoners. The following winter, a new Sioux lodge was brought to the area to make the prisoners more comfortable.

Once the Civil War ended, the community wanted to see the prisoners either charged or released. In April 1866, President Andrew Johnson ordered the release of the remaining 177 prisoners there. The people were sent to a reservation at Santee, Nebraska.

Overall, 73 prisoners died at Camp Kearney. They were buried in unmarked graves on the ridge of McClellan Heights. A cemetery also was located on the east side of today’s McClellan Blvd. at Hillcrest and Kenwood streets. It was eventually moved as the area was developed for housing.