Factories in the 1870s were vastly different from factories we know today. Most work was accomplished by hand, and equipment was often crude by today’s standards. John Deere operated out of rented quarters during his first year in Moline. His partner, Robert Tate, visited eastern factories, learned efficient processes, and ordered equipment for the erection of a three-story factory in Moline. When choosing a site for his new factory, Deere was looking for abundant waterpower, readily available sources of fuel, and navigable waterways. He found all three along the yet sparsely developed Moline waterfront.

Image Courtesy of John Deere Archives

The agricultural implements Deere was manufacturing were intended for hard use, and they needed to be able to withstand the work. With plowshares made of steel, plows became more durable, but producing individual uniform equipment was still a tall order.

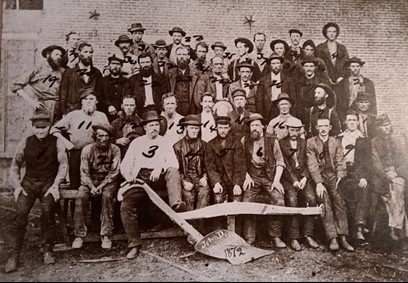

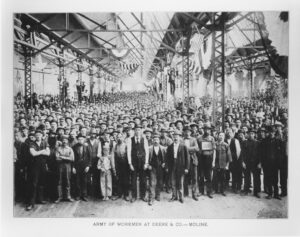

Deere & Co. Employees from 1872 Photo Courtesy of John Deere Archives

For a look into life in the factory at this time, long-service Deere employee John described his early days in the shop in 1874, as detailed in the book “John Deere’s Company: A History of Deere & Company and its Times,” by Wayne G. Broehl, Jr.:

“There was no whistle at this time, so a bell was rung when it was time to start work. In some parts of the shop, we had gas lighting. … In the blacksmith shop, they used torches when it got dark, and everyone had a hand kerosene lamp…

“In those days, everything was handwork, so iron and steel was transported from the Steel Storage to the shearers on shoulders and wheelbarrows, as we had no trucks at that time in which to haul this material around. There were 35 to 40 blacksmiths who worked at forges, most of them having a helper. … When the work in the blacksmith shop was completed, the stock was hauled to the fitting shop or the cultivator department.

“The parts used on the plows were made of iron and had no cutting edge, so such things as hanging and standing cutters had a steel edge welded on. At that time, we were building a wheel plow – the Deere Gang – and we made about four a day. A year later, they were made at a rate of ten per day. …

“At that time, we also made many Breaker Plows, and all were fitted with extra shares; thus, the plow was built first and then the share was removed, and another was fitted to the plow, after which both shares and the plow were stamped with a number. On other plows, we did not guarantee extras to fit.”

Kiel’s account illustrates the ways in which craftsmen of his time combined their efforts to manufacture individual pieces, without an assembly line. Each part was forged, cut, ground, polished and painted at a slow pace for precision.

Workflow improvements were made incrementally as decades passed, and by 1895, Deere orchestrated the company’s first survey of labor productivity in response to the recession caused by the Panic of 1893. The survey showed that more than eight million individual pieces were handled in more than 28 million operations over the course of a year, which told Deere they needed to simplify their processes. Fortunately, they were able to make the necessary changes and succeed.

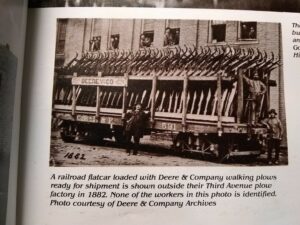

Railroad flatcar loaded with Deere & Co. walking plows (1882) Photo Courtesy of John Deere Archives

In the late 1800s, the United States experienced enormous agricultural growth. According to a National Department of Commerce Survey, there a 71% increase in the number of farms in the U.S., and each farmer would need to purchase his own equipment. John Deere’s company, in turn, grew substantially as well, in large part because of his steel plow that made land more profitable to manage.

Photo Courtesy of “John Deere’s Company” by Wayne Broehl and John Deere Archives

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, a large portion of the Deere & Co. workforce was Swedish and Norwegian. (The United Kingdom of Sweden-Norway was later dissolved into independent states in 1905.) In the United States, 1905 saw large numbers of people immigrating mostly from central, eastern and southern Europe, according to the book, “John Deere’s Company.” This was reflected in the makeup of Deere’s workforce, the book states, and at a factory managers’ meeting in 1912, it was disclosed that Deere employed large numbers of Belgians, Russians, Jews, Germans and Bohemians (mostly Czech).

According to internal policies written by the superintendent of Deere’s Plow Department, A.H. Head:

“We must depend on him (the immigrant) to handle the larger part of our rough manufacturing work and for all general roustabouting. This means that we must readjust our ideas to some extent. … The foreigner must be given credit for possessing a brain, and our aim should be to find the right key to manipulate it.

“The cause of our failure to secure success from this class of help is more frequently our own fault than it is that of the man employed. … He is anxious to learn, but usually unable to understand our language and does not secure a real understanding of what is required of him. Special efforts must be made to have him thoroughly understand what is wanted and to impress upon him the quality and quantity of the work required.

“He will respond to attention and considerate treatment more readily than his American brother, and appreciates a pleasant word of good fellowship more than we realize. If properly instructed, he takes pride in his labor and will strive to produce the best quality possible. … Many failures in the handling of foreign labor in the factories are due to lack of consideration being given to the training the men have had in their own country. … Remember that the Southern European is human and must so be treated.”

Did You Know?

In the early 1900s nearly all Deere & Co. employees either walked to work or took a horse-driven trolly. Housing located near their facilities would both attract new employees and retain current ones for a longer period of time. In October 1910 the company purchased fifty lots in East Moline on which to build houses that would be rented to employees. In 1918 and 1919 two apartment buildings were constructed in Moline for John Deere Plow Works employees.

Pictures courtesy of Housing for Recruits article in John Deere Tradition Magazine

In order to offer low-cost financing for employees who wanted to buy a house, the company organized the Moline Home Buying Syndicate made up of seven employees each representing a different John Deere factory or company in Moline or East Moline. According to the January 1919 issue of John Deere Magazine, twenty-one houses had been completed and ten more were under construction. An employee could hire his own architect and contractor and then submit his documents for inclusion in the program.

To obtain financing, 10% of the total cost of the house and lot needed to be paid when the contract was signed. The balance was to be paid in monthly installments based on $1 a month for each $100 financed. The average cost of these houses was $4,000. So, after a $400 down payment, the monthly mortgage payment would be $36. The buyer also needed to pay for taxes and insurance.

During 1918 and 1919 two apartment houses were built in Moine primarily to be rented to John Deere Plow Works employees. The apartments rented from $20 to $28 a month. The downturn in farm equipment sales and factory production during the 1930’s brought an end to Deere’s house building and financing programs. But at the outbreak of WWII, housing was again in short supply and the company built additional houses and apartments in both Moline and East Moline for either rent or sale to employees.

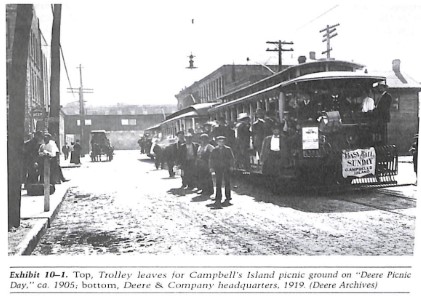

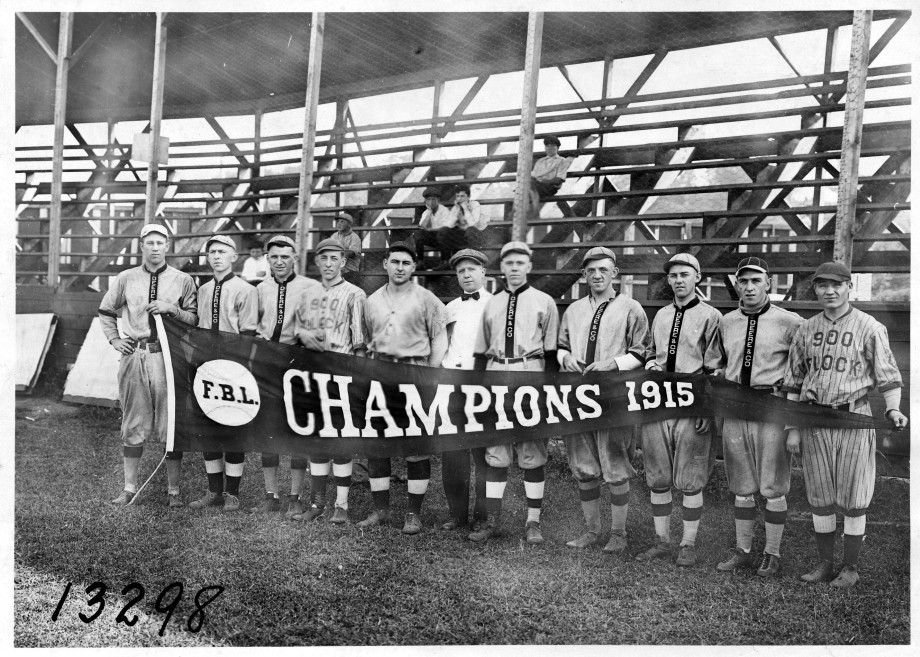

_________

Deere & Company also strived to build community within the organization, hosting events such as an annual picnic day, offering a factory league baseball team, and more. The photos below show employees taking a trolley to Campbell’s Island for a picnic day, and players who won the 1915 Factory League Championship. Sundays were a time to focus on family, religion and community gatherings. (Visit QC PastPort’s Campbell’s Island location to learn more about the island.)

Photo Courtesy John Deere Journal

Both John Deere and the City of Moline saw rapid growth during this period. The population grew from 7,390 people in 1881, to 25,000 people in 1910.

Photo Courtesy John Deere Journal

Late in 1858 John Deere was turning the management of the business over to his son, Charles. Charles had attended both Iowa College in Davenport and Knox College in Galesburg. He then attended Bell’s Commercial College in Chicago securing something like a postgraduate business degree. He was taking on the leadership role with both a solid education and his father’s solid advice.

In the winter of 1865, John’s wife Demarius died at age 60. A little more than a year later, John traveled to his native Vermont and married Demarius’s sister, Lusena Lamb. He was 61, she was 56.

In 1873 John became Moline’s second mayor and delt with prohibition, repair of sidewalks and streets, installation of streetlighting, sewer upgrades, and fire hydrants in the manufacturing and business areas of town. He served as President of the National Bank of Moline, a director of the Moline Free Public Library, and was a trustee of the First Congregational Church. He split his time in the warmer months between his home on the bluff called Red Cliff and his two farms. During the winter months, he and Lusena stayed in Santa Barbara, California. On his last return to Moline, he was clearly looking fragile and tired. He died at his home on May 17, 1886.

John Deere’s home Red Cliff courtesy of City of Moline

John Deere is remembered as a man who took one seemingly small idea and through hard work and perseverance, revolutionized agriculture in the Midwest and laid the foundation for what would become one of the most productive and successful companies in the world. We can be proud to say that much of the hard work that led to John Deere’s success happened right here in Moline, Illinois.